Some people consider it poor taste when atrocities in history are restructured and brought back to life for the cinema. Jean Luc Godard, for one, reprimanded Spielberg for ‘rebuilding Auschwitz’ in Schindler’s List. Alternatively, there is a danger in silencing re-tellings of history. There are lessons to be learned from the past. We must preserve the ghosts.

So many films done on World War II have been graphic; told forthrightly and provocatively. For example, Saving Private Ryan and Come and See, the stories of military battles and the Byelorussian occupation respectively, are powerful in how mercilessly confronting they are, in how they force you to look, and to witness. As history becomes smaller and further in our periphery with time, it threatens a danger of us forgetting. There is a confronting knowledge in this tactic, especially for the generations now that did not experience these events in their lifetime.

The Zone of Interest goes about the retelling of a Holocaust story in a very different way, breaching subtleties even more sinister than its more graphic peers. It confronts us with the reality of the ‘banality of evil’, a term coined by Hannah Arendt during the trial of Nazi Adolf Eichmann. Because this the truth about evil is startling mundane, and human. And for the Höss family in Jonathan Glazer’s movie, evil also has children, a lush garden that it cares over, and a tenderness for lilacs and beauty. The mundanity of the story we witness is what chills us to our core. We know very well what occurs just across the fence of their home, where Auschwitz is located, and we know what atrocities Rudolph Höss, the commandment of the Auschwitz concentration camp, is orchestrating.

We witness over the 105-minute film, an ostensibly ordinary family going about a very ordinary life, bordering on mundanity, whitewashed and sanitized. They rush to clean, to compartmentalize their space and their life from the garden of destruction they are cultivating just a hundred feet over; the very mind of ‘us and them’, the dangers of dehumanization at play, and its consequences. Despite their constant sanitization, however (Rudolph’s desperate act of chivying his children from the river and scrubbing them clean after finding a body part upstream, Hedwig’s demands of her Polish maid to clean a mess on the floor or she ‘could have her husband spread [her] ashes across the fields of Babice’), something is still rotting to its core. It’s rotting from the ground up. It has rotted Hedwig and her husband, and it’s rotting their children and the games they play. It’s rotting in the sparkling river that they swim by in their house, and threatening to track its dirty boots all throughout their house. And it comes close to rotting Hedwig’s mother when she visits but she can smell it in the air and runs away in the night.

They’ve tainted the very river they were bathing in; the very Eden they were so thoughtlessly enjoying. As long as they remain upstream, however, they cannot be contaminated by the nature that they tarnish. As long as they remain upriver, and sleep through the night, as long as the industrial noise of Auschwitz can lull into a white noise, the horrors will persist. However, Rudolph has seemingly forgotten that all of time and history flow forward, and our actions within them. He’s already marked his children with the rotting that has already eaten away at him. The dissonance, the sanitization, the refusal to look, it all has a cost. There is no upstream in a genocide.

The noise is another tremendously important aspect of this film. Since we rely so little on visuals to construct the terrors beyond the wall in our mind’s eye, Glazer relies entirely on the auditory to orchestrate this knowledge. This is how he communicates things we cannot see. Sound designer Johnnie Burn made a comprehensive 600-page document including events that occurred at Auschwitz, testimonies from witnesses, and a map of the camp so that the echoes and the sounds could be properly determined. Then he spent one full year building the sound library. The movie begins with us observing the family playing in a lush river and a verdant pasture in the summertime, with the sounds of birds and nature. But when we accompany them back to their home, we are introduced to disturbing industrial hums, gunshots, and yelling.

These sounds perpetuate your discomfort, while the family seems unbothered. It is background to them because they have been living there for so long. They are standing proverbially upstream, unaware that subconsciously it is rotting them, infecting them like a virus, and encompassing them like a vine. It contaminates their sleep (the daughter restlessly sleepwalking), and the grandmother is kept awake and alarmed. It contaminates even their play. The sound design seems to be an experiment in cognitive dissonance. How long into the movie until you realized you weren’t hearing the noises anymore? Until what seemed so intensely unsettling had become forgotten? Are you standing upstream?

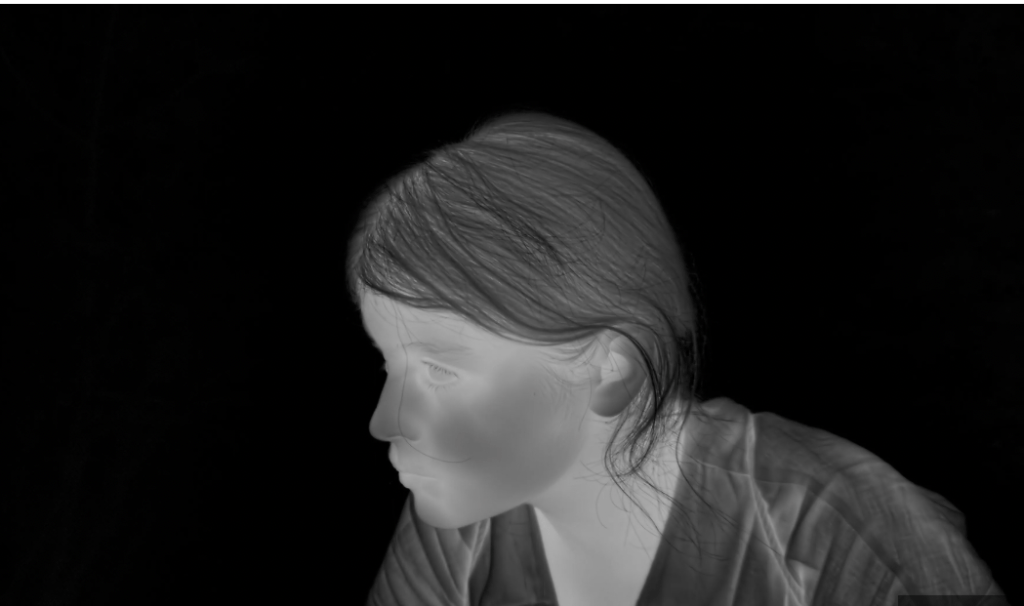

Another interesting choice Glazer made in this film was the utilisation of only natural lighting. This left him with an interesting problem of how to film the scene in the dark when the young Polish girl is distributing apples into the dirt for the prisoners of the camp. For this, he decided to use a thermal camera, which had a very interesting effect, of not only capturing the darkness of the time and the strength of what she was doing but also capturing her as more of an energy. It also reminds us that in times like these, when atrocities and evil are occurring in the stark light of day, goodness must be carried out in the darkness.

At the end of the movie, we are confronted with the juxtaposition of concepts of sanitation as presented throughout the film. We are transported to Auschwitz in its present condition; after all of the atrocities have occurred, and we see the cleaners come in to clean the windows, dust the ovens, and vacuum the floors. Compared to the Höss family desperately cleaning and sanitizing their own spaces from the contamination they were implementing around them, and trying to flee from the residue that clung to them, as if a testament to who they were and what they were doing. Like allowing the sounds of Auschwitz to dwindle to white noise, cleaning is a type of dissonance. However, we are reminded here that sanitization can not only be used to erase but to preserve.

You wonder, at the end of the movie, for a moment, when the commander is walking down the stairs and stops in his tracks to lean over and be sick if he’s realized the weight and reality of everything he has done. If he can suddenly hear the industrial humming, the hellish nightmare, and the gunfire; has he finally come to terms with the horrors? This is not why he retches, and it doesn’t matter if it is. After a moment he collects himself, puts his hat on, and continues walking. You realize your hope is futile, we already know how this ends. One moment of realization, of regret, of understanding, come and gone, it doesn’t matter. This is not enough to stop a genocide.